Art Thoughts, Week 36 -- Vuillard & Interiors

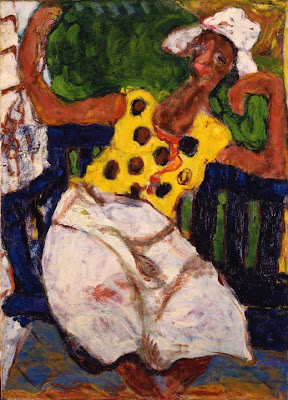

When Dr. Barnes bought this painting by Vuillard in 1912, Vuillard was forty-four years old. He had been spending the majority of his painting life indoors – at least as evidenced by many of his pictures. Even the exterior presence was normally viewed from inside, occasionally sneaking in only by permission of doors, windows and porches. Vuillard had also spent a great deal of his life in the house of his mother, a cottage industry seamstress. In Vuillard’s childhood, as in all of our childhoods, the psychological interiors and physical interiors tangle and overlap; they often emerge later on as muddled mirror images of each other. Considering the comparatively drawn-out period in which Vuillard matured into independence, he probably had a heightened sensitivity towards and intimacy with interior spaces. He enveloped himself (along with his paintings) in the warmth, intricacies, patterns and lights of French bourgeois existence, making many of his paintings feel like blurry, flocked dioramas. He even managed to convey a bit of the exterior’s openness into his interiors – his paintings rarely feel stifling.

James Castle was an American, born 1900, who drew and sculpted impetuously for decades on his family’s Idaho farm, spurred on mostly, it seems, by his inability to hear and speak. This rendered him largely unfit for the normal rigors of a rural life. But he coped through his drawings, which are simultaneously dim and dreamlike; lively and virtuosic. Most significantly, he was locked into a permanent interior by the fate of nature. Because of this, many of Castle’s explicitly exterior drawings feel like they are ordered and close interiors. And unlike the conscious, preferential choices made by Vuillard, who was drawn to an interior life and expression up to and through his adult life, Castle was required to make the most of what he was given.

An interesting comparison may be drawn, however. When I was first acquainted with the Vuillard in the Barnes collection, I didn’t at first notice the figure seated by the table. In fact, she really only came into form for me the fourth or fifth time that I really concentrated on the painting. She is a definite fixture, draped in the same brushwork which Vuillard used to convey both the lacey tablecloth; the chandelier; her needlework. Likewise, in many of Castle’s drawings, figures are drawn with the exacting, blocky layout and line as the buildings, rooms and barnyards he knew so well. Again, they are like fixtures in the space, portrayed as simply elements in a composition. Of course, this is an important, basic realization in any study of art – to draw a person is to draw, firstly, the same blocks, chunks and shadows as any other thing which occupies space. Many artists go on though and struggle to imbue their figures with that mysterious and elusive spark which makes them that much more alive – or more accurately, which appeals to our perceptions of aliveness, and attempts to convince us of its verity. And in many ways, we alone know the true intimacies, complications and machinations of our interiors. Though spill as we will (and do), we can never fully share the depth and breadth of our core selves. If they do rise to the surface, the most poignant translations are rarely prosaic; at times they are poetic, and often they are visual. And when we each have that “aha!” moment upon making a deep personal connection with another’s art (and seemingly, their soul), we might well wonder if we are looking into a diorama or a mirror.

(above, James Castle, The Big Attic Interior, date unknown). Thanks to Greg Kucera Gallery website. Read more...