Art Thoughts, Week 3 – Klee & Play

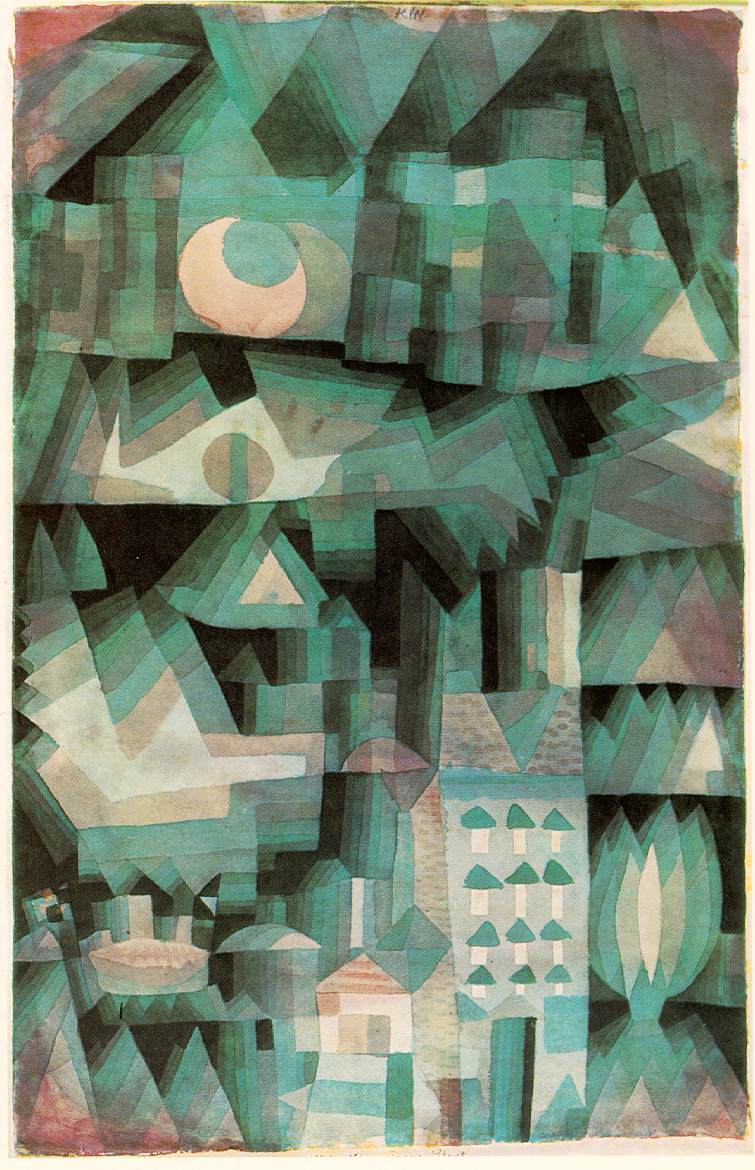

Village among Rocks (Ort in Folsen), Paul Klee (Swiss, 1879 – 1940), 1932. Gouache on canvas, BF 2520.

Blocks have always been one of my favorite toys. Even now, when at a house with small children, I will participate by building something with the often colorful pieces of wood. There’s something particularly satisfying about the fit and finish of a small structure made of wooden blocks, the feeling much like a greenhorn mason might have after finishing his first successful runs of bricks.

Drawing styles often imitate play styles. This makes sense; drawing is the first artistic impulse that most of us had, ham-fisted or not. And the Swiss artist Paul Klee has always been associated with the winsome and playful – though often with the appropriate dash of 20th century angst and satire mixed in (what would one expect of someone so close to fascism’s scowl?)

In the gouache drawing Village among Rocks (Ort in Folsen) the feel of the surface has several affinities with both blocks and rocks, both building materials. The subject matter is straight up against us, almost a sheer face of a cliff; the gouache surface is consistently mottled and weathered, evoking ancient alpine rock faces; and the color scheme is typical of multi-colored but dull rocks, or well-worn wooden blocks. The composition too, looks piled or built up, like a block structure. The shapes are erratic; jutting; all delineated by thin black lines, creating a web which runs to the borders. Here and there a door is suggested; a steeple; a low-sloping roof; a sharp flinty rock. Value in the drawing is highly consistent, though with subtle color shifts. There is blue-greys; dark clay-ochres and greyish-lavenders; teals and rust browns; dull periwinkle-steel and caucasian pinks.

Though the composition is somewhere between a web, a grid and a rockslide, the rusts and ochres (the slightly warmer colors) tend to pull away from the greys and blues (the chillier colors). So upon seeing the picture from a distance, a sense of a group of houses is created, but the effect is still of a village planted precariously on a sheer rock face. Many of Klee’s drawings evoke the sense of a diorama: this one feels like a backdrop to one.

There is a persistent ill-at-ease feeling that permeates this drawing as well. Since one cannot really be sure which shapes are the rocks and which are the houses, a slightly uncomfortable feeling exists, what one might get at dusk in an unfamiliar town. Of course, my mind tries to make sense of what it’s seeing here, but once some guesses are made, and the eyes follow the lines to interpret the space, most depth, scale or even angle is quickly lost among the weird shapes, jutting points and impossible juxtapositions. The edginess persists: this is not a cozy resort village. Doors open into rocks; some of the rocks seem to have roofs; the houses are all piled together.

This is all a bit children’s-spook story though; there is playfulness in this drawing too. Klee has toyed with the shapes in a way similar to one playing around and shuffling blocks: some of the angles were changed, painted over and the colors modulated; some of the black lines have moved and shifted direction; painted out. Play is in large part experimentation and learning, as is all forward-moving art, and that truth is evident in this drawing.