Art Thoughts, Week 25 -- Pascin & Craft

Most of us, at one time or another, were taught to draw by breaking what we were seeing down into individual shapes – triangles, squares, circles, cylinders, pyramids, rectangles and so on. This way, we were told, anything could be drawn; we could parse anything intellectually, visually rebuild it, then smooth off the edges: literally 2D sculpture as drawing. But this is not the only way of drawing, by any means. Instead, for example, one could use an unbroken line which caresses and undulates around an object, becoming a spatial, quivering depiction. Or, a drawing could be done completely in shaded patches, overlapping in different directions like so many screens or webs that eventually pile up into a specific shape or space.

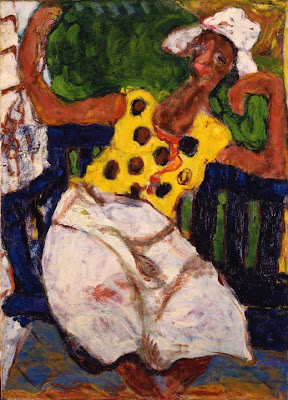

Pascin, at least in many of his exterior scenes, used a decidedly drawing-based style of painting, what I’d call line-and-wash, reminiscent of Kandinsky’s painting style. But overall, the particular shape which Pascin preferred using to construct or craft his compositions was the almond, or mandorla, shape. It can be found in the arching trunks of shade trees; the spindly legs of the horse’s and people’s limbs; and the foreshortened wagon wheels. It’s significant here that the almond shape is reminiscent of another iconic shape: the simple leaf. And in some ways, the manner in which Pascin has crafted his picture is akin to a pile of multi-colored leaves; all laying on top of, next to or overlapping one another; influencing and casting color and light between each other. And like leaves, which in a sudden gust of wind could blow away and completely rearrange, so it seems could the repeated elements in this painting.

And, as most artists eventually realize, that is about as concrete as a space – and light within that space – will ever get. Each moment brings change; everything from the most infinitesimal to the grippingly enormous, and they are all interconnected. Those who choose the exquisite torture of trying to depict these changes are constantly on the chase, like a dog after its own tail. (Thus the appeal of making up one’s own environment, with its more controlled set of variables – though this is just as elusive…how many of us have actually been successful in recreating the exact picture we began with in our mind?) There are, of course, significant numbers of these moments that do get successfully wrangled down; otherwise we’d have no artworks to speak of. But still, the space and forms are tenuous in Southern Scene – the feel is similar to a photograph in which shapes are blurred because there was movement during the exposure. Things in this painting fade in and out; there is air and room between elements, largely defined by color changes – much how a Fauvian Matisse feels. The leaf pile thus is able to breathe; to live.

This might be indicative of where and when this painting was made – likely out of doors, and on a sunny, breezy day. The crucial thing to realize though is that Pascin made deliberate choices about how he was going to craft his depiction, and because of those choices – the almonds; the dappled light; the breezy shapes – the painting feels wonderfully fresh. We know intellectually that this is a painting of a scene, not the scene itself. But still, we are somehow startled that it does not suddenly, despite being a resplendent butterfly pinned to a card, flutter its delicate wings and fly off.